LSSC’s website and news releases, as well as its Android and iPhone apps, all have references and connections to China. Sean O’Brien, the founder of the Yale Privacy Lab, which researches digital threats, examined the code of LSSC’s Android app and found it filled with Chinese digital certifications and references to Chinese tech services like QQ, Taobao and Alibaba. Apple requires all apps on its App Store to include custom privacy policies, which for LSSC appears to have been an afterthought. The title is “无标题文档,” Chinese for “Untitled document.”

Apple didn’t respond to a request for comment, but the LSSC app was removed from the store after NBC News asked about it. Android apps can be downloaded directly, without going through Google’s Play Store.

In another connection to China, LSSC’s website shares a domain with a company in Shenzhen that sells rechargeable battery devices. An employee said the company had sold charging devices to LSSC but had no other relationship. The employee didn’t offer a clear explanation of why they shared a web domain.

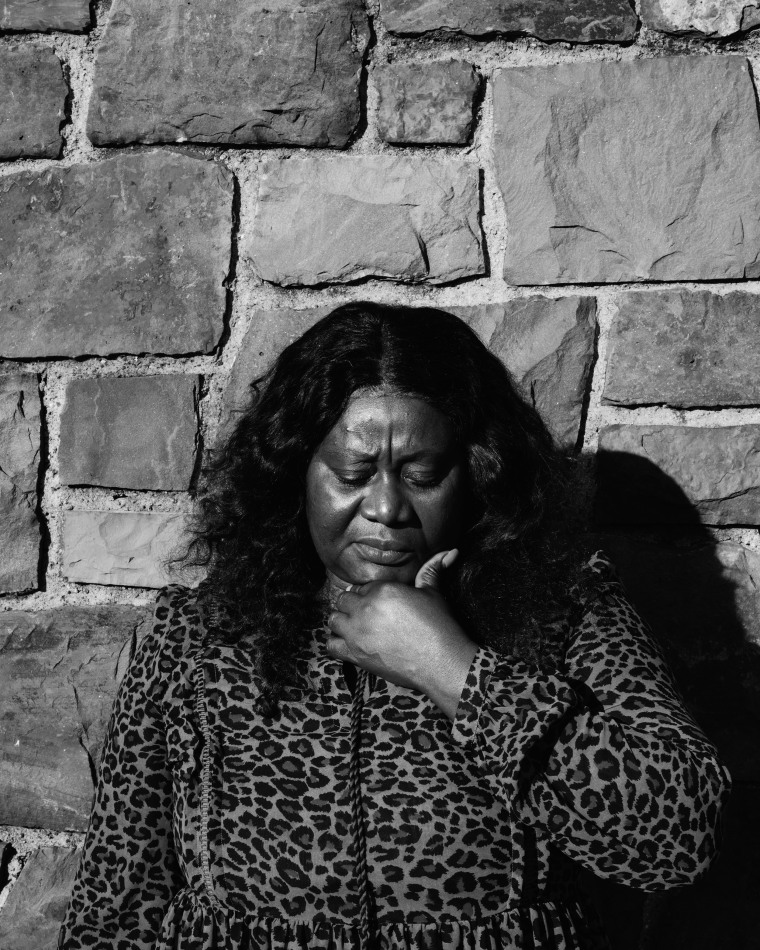

Patricia Livingstone, the group home manager from Philadelphia who invested $11,000, joined LSSC in April to help her 75-year-old mother in retirement. An LSSC manager instructed her to use not just the LSSC app but also Lightning Exchange, a related crypto investment platform, and a chat app that people who identified themselves as LSSC managers used to communicate with investors. Through the apps, the managers told her to log on at certain times to make specific trades. She began spending hours on the apps, communicating with other members and attending online training sessions. It was exhausting.

“I felt like I was in a cult, like a zombie,” said Livingstone, 35. “I was trading four times a day. It became my life, and I couldn’t sleep.”

Kumba Kenneth, Livingstone’s friend and co-worker who joined because of her, said she felt similarly “under control.”

“I go to work. I have to trade. Then it’s midnight. Look at the LSSC app to run your scooter,” said Kenneth, 44. “We were being manipulated.”

Tah-Ming Lee opened a $1,270-a-month LSSC office in Sandy Springs, Georgia, to host meetings and training sessions. It was funded by a manager named Paul he met on the chat app, but he said he had suspicions about whom he was talking to.

“We thought all these managers were AI,” Lee said. “They were writing in this weird way. They don’t sound like a normal human being.”

Lee said he couldn’t get a straight answer about how the scooters were rented, so he had a friend in Hong Kong check whether any LSSC scooters were zipping around. The friend said no.

In the earlier months of the company last year, Lee said, money was flowing in — he estimates having earned at least $40,000 from his initial $35 investment — making the operation appear legitimate.

But in recent weeks, investors trying to withdraw money from the app received messages saying the withdrawals were “pending.” The money never arrived. LSSC also asked people to pay an account verification fee of $75 to get their money, but members who spoke with NBC News said they refused.

Hoffman, the Arlington County police officer who began investigating LSSC in June, said the verification requirement appeared to be a “last-ditch effort” to squeeze money from desperate members before the scam collapsed.

Seeking payback

Hoffman said he understands how people presumed the scooter sharing app was real.

“We’re in this age of ‘be your own boss,’” he said. “You have DoorDash, Instacart, these legitimate businesses where you can make your own schedule.”

The lure of financial freedom attracted Mayson, the New Jersey man whose sister recruited him, to invest with LSSC. He attended company luncheons and parties and peered into a storefront in Oaklyn, New Jersey, a Philadelphia suburb, that was lined with scooters.

Oaklyn Mayor Greg Brandley had attended a ribbon-cutting for that store, where he announced that he had never heard of LSSC but said, “We just want to wish you much success.”

Brandley didn’t respond to requests for comment. The store appeared to be closed recently, and the business’ voicemail was full.

The Oaklyn Police Department said it is investigating reports of fraud regarding LSSC.

Mayson, who said he and his wife lost about $100,000, has joined a WhatsApp group for victims seeking justice. Some of the members, many of whom are West African immigrants, have filed complaints with law enforcement.

Mayson said he felt particularly manipulated by Vasey Salagbi, who identifies himself in videos as a regional LSSC manager. In one, Salagbi says he has over 1,500 members and proclaims the business is “not a sales scam.”